The first few weeks of “shelter in place” didn’t bother me much. I’m married, so I’m not totally devoid of personal contact. I often talk with my close friends by phone and over Facebook, and I’ve been catching up on overdue housework and getting a fair amount of writing done. But as of this last week, the lack of face-to-face contact with my friends and my sons is wearing me down. I can’t focus to write, my exercise routine went in the toilet, and I’m suffering from an overall feeling of frustration.

I know I’m not alone in these feelings. Some people battled depression at the beginning, some weathered it well for a while, but like me, are finding their coping skills wearing thin. Until the last five years, most of my “friendships” were workplace acquaintances. My co-workers and I got to know each other pretty well, but rarely socialized outside of the workplace. I had a close-knit family—my husband and two sons, my mother and my sister, with whom I was very close. That was pretty much all I needed.

My mother passed away almost twenty years ago, and my sister a little over a year ago. My sons have moved to another city about sixty miles away, though under normal circumstances, I see them almost every weekend. But my day-to-day support circle has dwindled to just my husband. Therefore, new friends with whom I share the joys and tribulations of the writing profession have become much more important to me.

So, I found the following article by Inga Popovaite, Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology, University of Iowa, very interesting. It was posted by EarthSky Voices in Human World, April 23, 2020, (www.earthsky.org). (Earthsky republished it from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license).

Dr. Popovaite writes:

Understanding isolation’s effects on regular people, rather than those certified to have ‘the right stuff,’ will help prepare us for the future, whether another pandemic or interplanetary space travel.

I was supposed to travel to “Mars” this month. The plan was to stay two weeks at the Mars Desert Research Station—actually in the Utah desert—to simulate human operations on the red planet. Eight of us were to live in a two-story cylinder, 24 feet (7 meters) in diameter. We would conserve water and put on mock spacesuits every time we ventured outside. (Image via George Frey/ Getty Images News/Getty Images, reprinted on www.earthsky.org.)

But, in an ironic twist, the coronavirus pandemic and the worldwide spread of social distancing put on hold our simulation of isolation on Mars.

My main goal had been to collect data for my dissertation. I research groups in space analog environments, isolated and confined places that share characteristics with human space missions. I’m especially interested in the way gender contributes to individuals’ influence within a group and how men and women manage their emotions in isolation and confinement.

(Image via David Howells/ Corbis Historical/Getty Images, reprinted on www.earthsky.org.)

(Image via David Howells/ Corbis Historical/Getty Images, reprinted on www.earthsky.org.)

I will not go to “Mars” this spring. As I am self-isolating at home, though, I keep thinking about what lessons for future space travel the current situation can provide. Astronauts have shared tips on how to survive long periods of loneliness and isolation. Maybe in return, the experiences of millions living under lockdown can offer insights into previously understudied social effects of isolation and aid future space travel….the more researchers understand the social effects of isolation on regular people – as opposed to those certified to have “the right stuff” – the better we will be prepared for the future, whether another wave of pandemic or interplanetary space travel.

Most group behavior research in space and space-analog environments focuses on leadership, cohesion, and conflict—factors that affect teams’ performance and their ability to complete tasks. It makes sense, as astronauts are first and foremost a team of co-workers on a specific mission.

But, by focusing on the professional level, researchers overlook other potential relationships between crew members – such as family ties or intimacy. It is not a minor detail: Interpersonal relationships can certainly change dynamics of group behavior. If you’ve ever shared a workplace with a romantic couple, for instance, you probably know there can be some drama.

So far, only one married couple has been to space. Researchers suggest that couples are better equipped to handle isolation because of mutual social support. Having couples on board makes the team feel closer as a whole.

However, anecdotal evidence from China suggests that divorce rates jumped after the quarantine. This factoid suggests that it’s not clear whether average real-world couples are better suited for isolation than single individuals.

Now, researchers like me have an opportunity to understand how couple dynamics influence life in isolation – including sex and sexuality, questions that NASA is not eager to address. While pregnancy can be dangerous, intimacy and sexuality can improve emotional and mental well-being over long periods of social isolation…. Men and women have the same general goal – to survive the pandemic and its aftermath – but they experience the quarantine differently. In most middle-class families, the traditional work-home divide is now gone, as both partners work from home. But women are still likely to spend more time running the household, including child and elderly care.

While at this stage there are no screaming toddlers in space, space-analog research shows similar trends of women taking care of other crew members. The widespread lockdown could allow researchers to get more data on how social norms and expectations about each gender—for example, who is supposed to offer more emotional support—influence behavior in mixed-gender groups in highly uncertain and stressful situations.

There is no doubt that coronavirus-caused social isolation will take a toll on individual and collective mental health. But staying home saves lives. Maybe this experience will also provide lessons on how to plan for future cities and social life on another planet.

As writers, we draw from our own experiences, even when creating fantasy or alien characters. So use this difficult time in your life to explore your own emotions and reactions, and those of the people around you, to lend more depth to your characters in crisis.

I took a trip to Arizona a couple of years ago, presumably to help a friend of mine with research for a book she was writing, but the landscape there inspired an entire alien culture for my third book (delayed release due to you-know-what).

I took a trip to Arizona a couple of years ago, presumably to help a friend of mine with research for a book she was writing, but the landscape there inspired an entire alien culture for my third book (delayed release due to you-know-what).

I can’t vouch for this particular community in Japan (

I can’t vouch for this particular community in Japan (

In evolution, it’s far easier to lose properties than to create something that didn’t previously exist. So snakes lost all their digits, horses evolved to use only one digit which forms a hoof, and others utilize two or three digits.

In evolution, it’s far easier to lose properties than to create something that didn’t previously exist. So snakes lost all their digits, horses evolved to use only one digit which forms a hoof, and others utilize two or three digits.  these elements, there is at least one organism on earth that can withstand extremes. Salinity and oxygen are two that readily allow the development of advanced life forms, so for the purposes of my blog, I will dismiss those. Given enough time, it wouldn’t surprise me to have dolphins, whales, and maybe octopi join us as sentient lifeforms (if they haven’t already, and we’re just too stupid to know it). If you don’t know why I included octopi, do some reading on these amazing creatures—my top pick for inspiration in alien life.

these elements, there is at least one organism on earth that can withstand extremes. Salinity and oxygen are two that readily allow the development of advanced life forms, so for the purposes of my blog, I will dismiss those. Given enough time, it wouldn’t surprise me to have dolphins, whales, and maybe octopi join us as sentient lifeforms (if they haven’t already, and we’re just too stupid to know it). If you don’t know why I included octopi, do some reading on these amazing creatures—my top pick for inspiration in alien life. People in the Atacama have a history of collecting water from the air. For hundreds of years, native people in the Andes harvested water by capturing the morning dew. They dug pits into the ground to hold buckets and made funnels from branches to channel water into the buckets. Lids made of branches and leaves kept the water from evaporating. The trap was left overnight and the water collected in the morning after dew formed. They have also been capturing water from fog for over a decade using screens that have very small mesh. The water in the fog condenses on the screens and drips into troughs below. Pipes carry the water to where it will be used. The idea caught on and now there are fog collectors installed in 25 countries in Africa, South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Asia. How’s that for a great world-building idea?

People in the Atacama have a history of collecting water from the air. For hundreds of years, native people in the Andes harvested water by capturing the morning dew. They dug pits into the ground to hold buckets and made funnels from branches to channel water into the buckets. Lids made of branches and leaves kept the water from evaporating. The trap was left overnight and the water collected in the morning after dew formed. They have also been capturing water from fog for over a decade using screens that have very small mesh. The water in the fog condenses on the screens and drips into troughs below. Pipes carry the water to where it will be used. The idea caught on and now there are fog collectors installed in 25 countries in Africa, South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Asia. How’s that for a great world-building idea?

share a sleeping area. Each pod has a recreation and eating area, and an adult lives in each pod with them. The children also have communal activities with children from other pods.

share a sleeping area. Each pod has a recreation and eating area, and an adult lives in each pod with them. The children also have communal activities with children from other pods. young males especially enjoy mock combat, though we have little use for that with our technology. It’s mostly a way to test each other’s strength.

young males especially enjoy mock combat, though we have little use for that with our technology. It’s mostly a way to test each other’s strength.

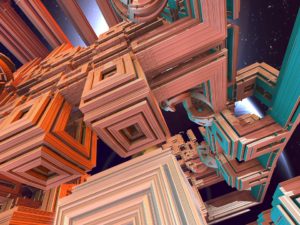

in habitats similar to those on 1-4. This is a picture from 6-4 near one of our mining sites. Some of them do have beautiful geologic formations.

in habitats similar to those on 1-4. This is a picture from 6-4 near one of our mining sites. Some of them do have beautiful geologic formations. S: I gather then that none of the planets you colonized had native sentient species.

S: I gather then that none of the planets you colonized had native sentient species. S: It sounds like you pretty much stripped your home world. How livable is it?

S: It sounds like you pretty much stripped your home world. How livable is it?

S: An orbital colony—like a space station?

S: An orbital colony—like a space station?

J: I find the air in the colony far fresher than what I’ve encountered on planetary surfaces. The atmosphere on a planet is difficult to control over a broad area. It becomes contaminated with dirt, dust, air-borne microbes. I usually wear a filtration device when I’m outside one of our habitats. Our homes are beautiful and very comfortable.

J: I find the air in the colony far fresher than what I’ve encountered on planetary surfaces. The atmosphere on a planet is difficult to control over a broad area. It becomes contaminated with dirt, dust, air-borne microbes. I usually wear a filtration device when I’m outside one of our habitats. Our homes are beautiful and very comfortable.

happy to say, we’ve made tremendous progress in that regard. Ka’Ran has a very stable ecosystem, and even our High Order has embraced the need to preserve it.

happy to say, we’ve made tremendous progress in that regard. Ka’Ran has a very stable ecosystem, and even our High Order has embraced the need to preserve it. rewarding. As it turned out, their advice was wise, since I make a good, dependable income. The robots I design are used as artificial workers for maintenance and building, fighting intense fires, and cleaning up bio and chemical hazards where use of protective gear is too cumbersome or dangerous for live workers.

rewarding. As it turned out, their advice was wise, since I make a good, dependable income. The robots I design are used as artificial workers for maintenance and building, fighting intense fires, and cleaning up bio and chemical hazards where use of protective gear is too cumbersome or dangerous for live workers. O: It is because they do not live like this. They have elegant homes on other planets, or live in opulent orbiting colonies.

O: It is because they do not live like this. They have elegant homes on other planets, or live in opulent orbiting colonies.

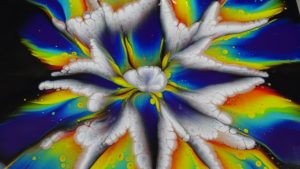

S: Oh, these are beautiful.

S: Oh, these are beautiful.  find a way to be together for several years before Oba had the opportunity to emigrate to Dudra.

find a way to be together for several years before Oba had the opportunity to emigrate to Dudra.  S: It is, though we are fighting our own battles with pollution. Plus, though our people now know that sentient, advanced species inhabit other worlds, it is a recent discovery for us. Until a few years ago, many Earthers refused to believe that was possible, and many are still not comfortable with the idea. We often have problems with discrimination between races, differing religious beliefs, and differing lifestyles among our own people that lead to violence. There are aliens living among us, but they are human, or have taken human form, so that they blend in well. The only non-human aliens here at present are those serving in temporary ambassadorial roles, and they are well-guarded by our police forces.

S: It is, though we are fighting our own battles with pollution. Plus, though our people now know that sentient, advanced species inhabit other worlds, it is a recent discovery for us. Until a few years ago, many Earthers refused to believe that was possible, and many are still not comfortable with the idea. We often have problems with discrimination between races, differing religious beliefs, and differing lifestyles among our own people that lead to violence. There are aliens living among us, but they are human, or have taken human form, so that they blend in well. The only non-human aliens here at present are those serving in temporary ambassadorial roles, and they are well-guarded by our police forces. N: She was a speaker at a trade conference here on Dudra several years ago. I attended and was impressed by what she said. We felt a deep bond almost immediately, but Oba had to keep it secret because of the religious stigma on her world. If it hadn’t been for that, I would have moved there. Ka’Ran is a water world of great beauty, with a thriving culture of visual and performance art, literature, and architecture. Dudra is quite bleak by comparison.

N: She was a speaker at a trade conference here on Dudra several years ago. I attended and was impressed by what she said. We felt a deep bond almost immediately, but Oba had to keep it secret because of the religious stigma on her world. If it hadn’t been for that, I would have moved there. Ka’Ran is a water world of great beauty, with a thriving culture of visual and performance art, literature, and architecture. Dudra is quite bleak by comparison.

S: You had told me you have seven children. Tell me more about them. Are some adults already?

S: You had told me you have seven children. Tell me more about them. Are some adults already?

C: Compared to what appears to be the norm in the United States, from what I have seen in image transmissions. It is hard for me to imagine a large house with a lot of ground around it, and only one small family unit living in it. It seems quite wasteful. Our living arrangements are much more like what I have seen in large Asian cities—large communities of smaller apartments. This is a picture of a complex in the capital city where I live when I am not traveling.

C: Compared to what appears to be the norm in the United States, from what I have seen in image transmissions. It is hard for me to imagine a large house with a lot of ground around it, and only one small family unit living in it. It seems quite wasteful. Our living arrangements are much more like what I have seen in large Asian cities—large communities of smaller apartments. This is a picture of a complex in the capital city where I live when I am not traveling.

C: It is significantly worse than normal for the last few centuries. Our planet goes through epoch cycles, and we are approximately twenty sun-orbits into the current epoch. Our volcanoes are normally active, but once each five thousand orbits, another planet in our system, Kitrong, reaches apogee in relation to Orozh, and it triggers an extreme level of activity. It is something we knew of well ahead of time and have prepared to deal with. We have relocated people and animals from the volatile areas to safer zones. We had built new towns and facilities in advance of the onset of increased problems. But there is still much work to do because of the greater concentration of population in certain areas.

C: It is significantly worse than normal for the last few centuries. Our planet goes through epoch cycles, and we are approximately twenty sun-orbits into the current epoch. Our volcanoes are normally active, but once each five thousand orbits, another planet in our system, Kitrong, reaches apogee in relation to Orozh, and it triggers an extreme level of activity. It is something we knew of well ahead of time and have prepared to deal with. We have relocated people and animals from the volatile areas to safer zones. We had built new towns and facilities in advance of the onset of increased problems. But there is still much work to do because of the greater concentration of population in certain areas. C: Yes, of course, it is hotter than Earth in most areas. At the same time, in areas where there has been limited volcanic activity for the past one hundred sunors or so, lush vegetation has developed, much like the volcanic islands in your Pacific Ocean. However, like your Pacific islands, the land mass of each one is relatively small, so the populations are limited there. We have four main continents, one about the size of Asia, two about the size of South America, and one a little smaller than Antartica. Most of the rest of our landmass is scattered across the planet in smaller sub-continents and connected island chains. Orozh is smaller than Earth, but a total of seventy percent of our surface is land rather than water, so we have little open water in the form of oceans, but a number of smaller seas. During low tide on one side of the planet, you can walk between many of the islands that are separated during high tide.

C: Yes, of course, it is hotter than Earth in most areas. At the same time, in areas where there has been limited volcanic activity for the past one hundred sunors or so, lush vegetation has developed, much like the volcanic islands in your Pacific Ocean. However, like your Pacific islands, the land mass of each one is relatively small, so the populations are limited there. We have four main continents, one about the size of Asia, two about the size of South America, and one a little smaller than Antartica. Most of the rest of our landmass is scattered across the planet in smaller sub-continents and connected island chains. Orozh is smaller than Earth, but a total of seventy percent of our surface is land rather than water, so we have little open water in the form of oceans, but a number of smaller seas. During low tide on one side of the planet, you can walk between many of the islands that are separated during high tide. C: The unstable regions are survivable, but far less comfortable. Those living there have to move often to find safe homes. They normally work at jobs assisting scientists who study planetary geology, or in positions providing services to others living there. The offending male may never return. His children may seek housing and jobs in the secure areas once they reach adulthood. The spouse of an offender may also seek separation from her mate, and may elect to take minor children with her. If it is granted, she would have to seek a job and housing to support the family. In some cases, if the male is honorable, he will grant the separation and still agree to provide support for the family.

C: The unstable regions are survivable, but far less comfortable. Those living there have to move often to find safe homes. They normally work at jobs assisting scientists who study planetary geology, or in positions providing services to others living there. The offending male may never return. His children may seek housing and jobs in the secure areas once they reach adulthood. The spouse of an offender may also seek separation from her mate, and may elect to take minor children with her. If it is granted, she would have to seek a job and housing to support the family. In some cases, if the male is honorable, he will grant the separation and still agree to provide support for the family.